Documentary filmmaker Anna Broinowski gets a rare glimpse of the North Korean film industry.

While some argue that Hollywood is the world’s largest propaganda machine, others believe it operates without an agenda but is simply a reflection of the broader culture. No doubt it is a place where creative decision-making is often dictated by market forces, and establishment values tend to be the norm, but government interference is limited and political messaging is rare. The same cannot be said of the North Korean film business, commonly considered the largest state-run propaganda machine in the world.

Cultivated under cinephile and Supreme Leader Kim Jong-Il, over the past 30 years the industry has produced some of its finest films, including its biggest hit, Pulgasari, a “Godzilla”-influenced giant monster movie. It was directed by South Korean filmmaker, Shin Son-Ok, who the Supreme Leader kidnapped in 1978, shortly after kidnapping his estranged wife, actor Choi Eun-Hie. Reunited in the North, the couple toiled in a gilded cage for 16 years under Kim, who employed them to raise the country’s profile at international film festivals.

“On the Art of the Cinema,” by Kim Jong-Il, is a bible among North Korean filmmakers. In it, the Supreme Leader takes credit for inventing the multi-camera shoot, and offers helpful hints for actors: “The better the actor looks, the harder he should work on his ideological development to improve his screen face.”

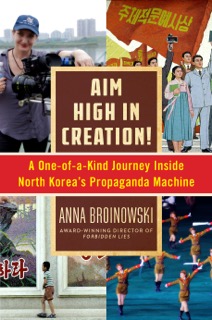

Another encouraging bromide, “Aim high in creation!” gave documentary filmmaker Anna Broinowski the title of her 2013 movie, a Michael Moore-ish chronicle of her attempt to use Kim’s cinematic principles to make a protest film.

Based on her movie and sharing its title, her book is a rare look behind the scenes of an industry mostly unknown to the west. An enjoyable and informative read, it appears to be an edited variation on a diary kept while filming. As such, Broinowski reveals something of herself recalling her first flight into Pyongyang when she becomes highly suspicious of an inquisitive and overly friendly flight attendant, then later realizes she was overreacting.

“Democracy has taught us to look for the lies,”Broinowski writes, trying not to jump to conclusions about a land she’s only ever known through the eyes of its enemies – a place of gulags and crushing poverty on the brink of starvation, dependent on the mercy of delusional dictators.

The daughter of the former Australian ambassador to Seoul, Broinowski was born in Tokyo and grew up in various Asian cities on her way to becoming a filmmaker. Her 2007 documentary, “Forbidden Lie$,” is about author Norma Khouri who wrote a fraudulent memoir about a young Muslim woman in love with a Christian soldier who is killed by her father in an honor killing. In “Aim High,” Broinowski includes autobiographical bits about her failed marriage, her teen-aged daughter, her aunt—famed anti-nuke activist Dr. Helen Caldicott—as well as the time she acted opposite Cate Blanchett. While you could call them personal touches, some might find them a distraction from the book’s more exotic premise.

Early on, Broinowski is met by Miss K., her North Korean minder, at the Yangakkdo Hotel, a cavernous lobby of green marble with a tower full of empty rooms upstairs. K. is a stern, middle-aged woman with chopped hair, the first in a long line of those who will determine how much latitude Broinowski will be permitted while in Pyongyang. Although she has done well for herself, K’s success seems to stem from rigorously following the party position and knowing the limits of her power. As the front line against evil capitalists who mean to present her country in its worst light, K. has seen more of the west than most, and seems to embody a stew of envy, pride, frustration and complacency.

Miss K.’s opposite is Sun Hi, another character that hops off the page—a bubblegum smacking twenty-something translator who, as far as her elders are concerned, asks too many questions about the west. One of Broinowski’s collaborators, film composer, Comrade Pei, embraces the chance to work with a foreigner, shedding the guarded interest worn by most of his colleagues. Comarde Pak, Kim Jung-Il’s favorite filmmaker, is standoffish at first, but gradually comes to mentor Broinowski. Through him and the others it becomes clear that two years into the reign of Kim Jung-Un, the new Supreme Leader does not share his father’s enthusiasm for movies.

At Pyongyang Studio, Broinowski tours the back lot and pitches veterans of the industry on her short film called “The Garden,” which will use their cinematic techniques to convey a political message about protecting Sydney Park from energy developers. Needless to say, the veteran filmmakers are intrigued enough by the strange proposal to give her the green light. Not only will they consult with her in pre-production but also will allow her to film them at work for her documentary.

While shooting at the U.S.S. Pueblo, an American spy ship captured in 1968 and held as a symbol of country’s dominance over the U.S., Broinowski is recruited into playing the wife of an evil American portrayed by an actor named Dresnok, son of James Joseph Dresnok, an American defector from the 1960s. A G.I. who hoped to escape punishment for misdemeanors in South Korea, he wound up staying in the North and becoming a famous movie bad guy instead. Today, his sons carry on the family tradition.

“Filmmakers are family” is a sentiment expressed early in “Aim High,” suggesting a people united not buy language or politics, but something deeper. A feeling of kinship streams through the book, forming a powerful, albeit fleeting, bond. Returning to the hotel after a final celebration, Broinowski’s shuttle turns down previously untraveled roads to places hidden away from the staged backdrops along the usual path. As she implores her new friends to join her at the hotel for a drink, one by one they are dropped off; the first near a dark and deserted cul-de-sac tenement with broken windows, another, Comrade Pak, by a stretch of dirt and barbed wire, broken down buildings in the distance. “When will I ever see you again?” he asks her, his voice shaking. But they both know the answer.

Kim Jung-Un has imprisoned over 200,000 of his people since assuming power in 2011, including U.S. student Otto Warmbler who was sentenced to 15 years hard labor last March for stealing a propaganda poster. Obama responded with new economic sanctions, but it didn’t stop North Korea from conducting nuclear tests in September, drawing worldwide condemnation. The situation is further destabilized by Trump suggesting Japan and South Korea develop nuclear weapons to counter the North.

Toward the end of the book, during a trip to the DMZ, Broinowski is surprised to find a Garden of Eden, an accidental nature preserve in the most heavily guarded strip of land on Earth. “Ma’am, just as you and I can stand here smiling at each other, I hope we can forge a new peace between our countries,” a young guard tells her. It’s a deceptively complicated sentiment. What about the old peace? Are Australia and North Korea at war? It illustrates that no matter how warm the words, the gap remains enormous. And while no one book or movie can span it, just by putting a face to the place, “Aim High in Creation!” offers a step in the right direction.

Aim High in Creation! By Anna Broinowski.

The Director is the Commander by Anna Broinowski – the book about making Aim High in Creation!