The first major exhibition in the United States of photography by Japanese artist Ishiuchi Miyako, as well as the first time in many of these works are on view, Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows at the Getty includes nine of her photographic series, that originated during the 1970s.

Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows runs until February 21, 2016, at the Getty Center.

Press release:

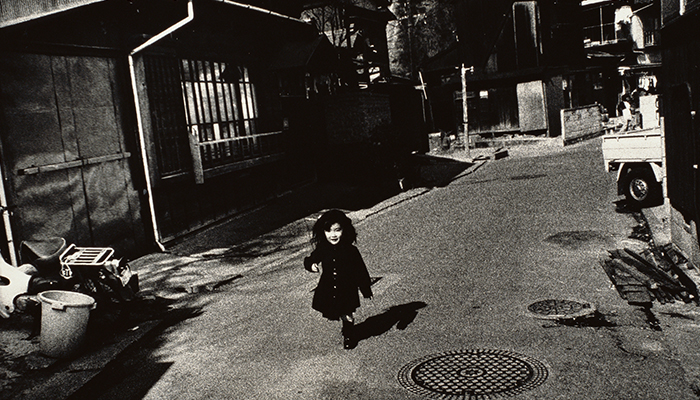

In the 1970s Ishiuchi Miyako shocked Japan’s male-dominated photography establishment with Yokosuka Story, a gritty, deeply personal project about the city where she spent her childhood and where the United States established a naval base in 1945. Working prodigiously ever since, Ishiuchi has consistently fused the personal and political in her photographs, interweaving her own identity with the complex history of postwar Japan that emerged from the shadows cast by American occupation.

This exhibition is the first in the United States to survey Ishiuchi’s prolific career and will include photographs, books, and objects from her personal archive. Beginning with Yokosuka Story (1977-78), the show traces her extended investigation of life in postwar Japan and culminates with her current series ひろしま/hiroshima, on view seventy years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The J. Paul Getty Museum thanks the Japan Foundation and Shiseido Co., Ltd., for their support of this exhibition.

Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows

Few Japanese women have been active in photography and many have had difficulty sustaining a career. An independently working artist, Ishiuchi Miyako has been a trailblazer for the past 40 years, with an impact on younger generation, as seen in the sister exhibition The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography, also on view at the Getty Center until February 21, 2016. This supporting exhibition features works by five contemporary photographers born in Japan who emerged in the 1990s and 2000s: Kawauchi Rinko, Onodera Yuki, Otsuka Chino, Sawada Tomoko, and Shiga Lieko. More information below.

Ishiuchi Miyako’s works are displayed chronologically, starting with 1976 – 77 in Yokosuka, the city where she grew up. It was a US naval base, and so throughout is the notion of Americanization and its intrusive influence. The relationship between Japan and the US can be seen in her works, that chronicle a personal history alongside the history of Japan during the postwar era.

Untrained, employing trial and error, her background was in textile design, so full grain and texture is essential to her process.

“I actually prefer to print than taking photos. I love the dark room. I love the graininess. Finally with Hiroshima I made it to color.”

There’s a length and depth of exploration of Yokosuka as her subject. “I finally resolved it with Yokosuka Again. I was exposed to America a great deal, so for better or worse there’s a lot of America in me.”

At times she used 20 meter roll of print paper and cut it, printing on this large roll and cutting it down. “The reason I love roll printing is that it’s exactly the same as dying a roll of fabric. For me the prints are physical, not conceptual. All these prints on the walls represent time I spent in the dark room conceiving images. In my mind, the labor was like a marriage. The personal was much stronger than the political. For me everything begins with my personal experience.”

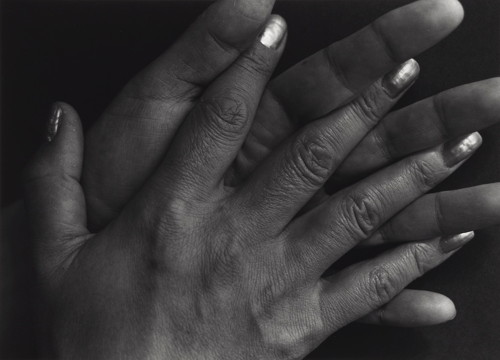

“When I turned 40 I contemplated my next move. I landed on a project that to get examined age and time as mapped on the body. I never thought I’d live to 40. Suddenly I was 40!”

For On the Body, Ishiuchi trained her camera to capture close up images of hands and feet. “I saw the body as the repository of the invisible – time and space are made visible on the body.”

She charted forty years of time etched onto women’s bodies. There’s a sense of melancholy evident in this exhibition. “In Japan, not everybody wanted to look at the time etched on women’s bodies. Withered, scarred – no longer youthful…Emotion and suffering — that’s what I was trying to capture. I was compelled by the body embraced by time. I’m interested in capturing what’s beyond the scar. If you see scar that means you are alive. Scars are representative of memory, akin to an old photo, just like old photographs tell that story once again.”

For one series she turned to polaroid snap shots. “I really enjoyed Polaroids — it’s a portable dark room.”

After success at the Venice Biennale, where she was representing Japan in 2000, Ishiuchi was approached to photograph Hiroshima. Of course, this year is the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Ishiuchi Miyako has been photographing objects and clothing from Hiroshima since 2007, using a mixture of approaches and also adopting color printing for the first time. Here she uses light boxes to show how much life is left in these items as they float in light and space.

The majority of the garments once belonged women — a few were owned by men. “I had never been to Hiroshima myself. So many photographers had. I figured there wasn’t anything left to photograph. It was also a world of black-and-white, but all these garments were so colorful and so fashionable.”

“I was accused of approaching Hiroshima as a social issue. I was accused of beautifying and glorifying these items. I said ‘These items were more beautiful before the bomb.’”

Ishiuchi remarked that Hiroshima had been boxed in by the male gaze. “I think I made a discovery. Every year people donate more cherished objects, so the post war is not over. I plan to keep photographing.”

Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows

On view until February 21, 2016, at the Getty Center.

~~~

The history of Japanese photography, long dominated by men, experienced a dramatic change at the turn of the 21st century. Challenging the tradition that relegated women to the role of photographic subject, a number of young women photographers rose to prominence during this period by turning their cameras on themselves. The resulting domestic, private scenes and provocative self-portraits changed the landscape of the Japanese art world. The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography, on view at the Getty Center October 6, 2015 – February 21, 2016, features works by five contemporary photographers born in Japan who emerged in the 1990s and 2000s: Kawauchi Rinko, Onodera Yuki, Otsuka Chino, Sawada Tomoko, and Shiga Lieko.

“These photographers bring a variety of approaches to their explorations of living in contemporary Japan and how they observe and respond to their country’s deep cultural traditions,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “From quiet morning rituals to scenes of matchmaking and marriage, this body of work provides a rich perspective on Japan’s ongoing examination of its cultural uniqueness and place in the wider world.”

As these younger photographers began to emerge at the end of the 20th century they were often viewed collectively and their work labeled onnanoko shashin, or “girl photographs,” despite their wide-ranging aesthetics and interests. This term, coined by critic Iizawa Kōtarō, was largely perceived as derisive, though some considered it a celebration of these women’s achievements. Countering the idea that “girl photography” could define a generation of practitioners, The Younger Generation showcases the breadth of work made by five midcareer photographers during the past twenty years. Selected images from one series by each of the five photographers will be featured in the exhibition, including recent acquisitions of photographs by Sawada Tomoko and Shiga Lieko made possible by the support of the Getty Museum Photographs Council.

The Photographers:

In 2001, Kawauchi Rinko burst onto the Japanese photography scene with her signature snapshot style of photographing moments of everyday life that frequently escape notice. Using color film and often employing a 6×6 cm Rolleiflex camera, she presents the world around her in quiet, fragmentary scenes, as if suspended in a dreamlike state. In the featured project Cui Cui, named after the French onomatopoeia for the twitter sound made by birds, Kawauchi concentrated on the passage of time as it relates to her family and hometown. Some photographs feature ordinary objects and everyday rituals such as meals and prayer, while other images record significant events that constitute turning points in Kawauchi’s life.

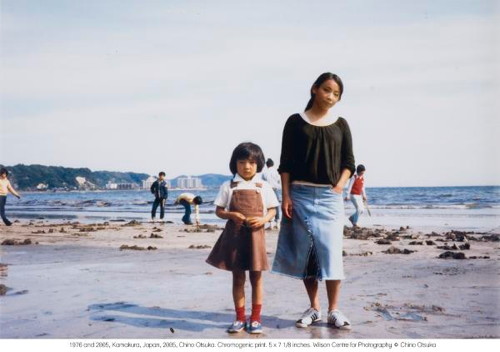

Born in Tokyo, but based in France, Onodera Yuki pursued photography after her disenchantment with the fashion industry. Interested in subverting the notion that photography represents the world accurately—the Japanese word for photography, shashin, translates as “to copy reality”—Onodera uses the medium to generate surrealistic images that defy reality. On view in the exhibition will be photographs from her series Portrait of Second-hand Clothes, wherein Onodera repurposes garments she collected from Dispersion, an installation by the artist Christian Boltanski that contained large piles of clothing for visitors to take home and “disperse.” Onodera photographed each piece against an open window in her apartment in Montmartre, and her use of flash enhances the ghostlike quality of the garments. Caught between two cultures for much of her life after leaving Japan to study in England at the age of ten, Otsuka Chino draws upon the intersection of her Japanese and British identities for many of her photographic projects. The “double self-portraits” from Otsuka’s series Imagine Finding Me, a selection of which will be featured in The Younger Generation, were motivated by her curiosity about the prospect of speaking with her younger self. With the help of a digital retoucher, Otsuka seamlessly inserts contemporary self-portraits into old photographs of herself from a family photo album. The results combine pictures from different ages and moments in her life. In this context, the photograph acts as a portal to the past, a time machine that allows the artist to become a tourist in her own memory.

Born and raised in Kobe, Japan, Sawada Tomoko has used self-portraiture to explore identity. She transforms into various characters with the help of costumes, wigs, props, makeup, and weight gain, all of which drastically alter her appearance. Her work—a cross between portraiture and performance—plays upon stereotypes and cultural traditions in order to showcase modes of individuality and self-expression. Her project OMIAI♡, recently acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum, includes thirty self-portraits, each one made in the same photo studio but intended to represent a different kind of woman. These images mimic photographs traditionally produced as part of the Japanese custom of omiai, or a formal meeting that occurs as part of the arranged marriage tradition. This unique set of OMIAI♡ includes vintage frames selected by Sawada to represent how such portraits would traditionally be displayed in the windows of local photo studios in Japan.

“Sawada’s playful, charming self-portraits belie a deeper commentary on her culture,” says Amanda Maddox, assistant curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum and curator of the exhibition. “With OMIAI♡ she reminds us how such traditions still play a significant role in Japanese society.”

In her practice, Shiga Lieko works with local communities, immersing herself in them and incorporating their histories and myths into her photographs. In 2008 Shiga moved to the Tōhoku region in northern Japan, a largely rural area known for its association with Japanese folklore. Working out of a small studio in Kitakama, she became the official photographer of the town, documenting local events, festivals, and residents. After much of Kitakama was devastated by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Shiga continued to photograph, recording the impact on the land and people. Made between 2008 and 2012, the series Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore) showcases the chaos and mysteriousness of this strange place. With a history associated with mythology, natural disaster, and trauma, Kitakama resembles an otherworldly, postapocalytic site. Six works from Rasen Kaigan will be on display, including photographs made after the disaster in Tōhoku, during which Shiga was forced to flee her home.

The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography, is on view October 6, 2015 –February 21, 2016 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. The exhibition is curated by Amanda Maddox, assistant curator in the Museum’s Department of Photographs.

Related events include a panel discussion titled Contemporary Japanese Photography: A Reaction Against “Girl Photography” with Sawada and Shiga, moderated by Kasahara Michiko, chief curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, on Thursday, October 15 at 7p.m. at the Getty Center.

The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts that includes the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation. The J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs serve a varied audience from two locations: the Getty Center in Los Angeles and the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts to 1900, as well as photographs from around the world to the present day. The Museum’s mission is to display and interpret its collections, and present important loan exhibitions and publications for the enjoyment and education of visitors locally and internationally. This is supported by an active program of research, conservation, and public programs that seek to deepen our knowledge of and connection to works of art.

Visiting the Getty Center

The Getty Center is open Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. It is closed Monday and most major holidays, open on July 4. Admission to the Getty Center is always free. Parking is $15 per car, but reduced to $10 after 5 p.m. on Saturdays and for evening events throughout the week. No reservation is required for parking or general admission. Reservations are required for event seating and groups of 15 or more. Please call (310) 440-7300 (English or Spanish) for reservations and information. The TTY line for callers who are deaf or hearing impaired is (310) 440-7305. The Getty Center is at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California.Additional information is available here.