In 1987 Paul Verhoeven’s satirical sci-fi action picture RoboCop shocked and thrilled audiences with its deliciously seditious take on corporate American and US law enforcement. In it the Dutch filmmaker presented a grim and dystopic vision of Detroit in the not-too-distant future, crippled by rampant crime and under siege by violent criminals. Rated-R, the darkly comedic drama is notable for its biting social commentary as well as numerous quotable lines of dialogue and outrageously sadistic scenes. A modern classic, RoboCop still holds up today, especially considering that few mainstream studio releases venture beyond the safe PG-13 rating zone.

In 2028, multinational conglomerate OmniCorp is forging new ground with high-tech robot technology, providing drones for military use overseas. OmniCorp is keen to bring their controversial technology stateside, but face prohibition. When Alex Murphy (Joel Kinnaman)—a loving husband, father and decent cop—is critically injured in the line of duty, OmniCorp leaps at the chance to launch their a part-man, part-robot police officer on the streets and gain lucrative government contracts. But what happens when you put a man inside a machine?

Commissioned to tackle a 21st century remake, Darren Aronofsky and David Self (as director and writer, respectively) were on board as far back as 2005. Eventually Brazilian filmmaker José Padilha (renowned for 2007’s Elite Squad—winner of the Golden Bear at the 2008 Berlin Film Festival) was enlisted to direct the first film in this reboot of the three-film franchise. Delivering a PG-13 picture with a rumoured $130 million budget was reportedly part of the deal.

“Here is the trick,” explains Padilha. “We’re trying to make a movie that talks about serious things, but at the same time we want to reach a broad audience, so you have to strike a balance. It’s all about tone. You have to be able to show, visually, the drama of this guy who doesn’t have a full body, who is a robot. You also have to show him in dramatic scenes with his family that make the audience want to cry. Then you have to have great action set pieces, and have fun, have jokes and light moments. We struck that balance by bringing an irony into the film, which is in the original RoboCop anyways.”

The director states he loves the first movie. “It’s true—Hollywood ran out of original ideas for stories a long time ago,” he laughs. “The original RoboCop is, as we all know, an iconic movie; a classic. Aesthetically bold in its use of violence. But I think, first and foremost, for me it created a character that encapsulated an idea that is really sophisticated. The idea that there is a connection between the automation of violence—in law enforcement and war—and fascism. That, to me, is the heart and soul and the reason to watch RoboCop. I am not trying to do the first movie again.”

Rather than a remake, Padilha appears to be striving to emulate its spirit. He adds, “I think we were very faithful to the original movie, both in the thematics and also in the tone.”

Star of the film, Joel Kinnaman, chimes in with his comment, “It definitely has a strong political element to it, but it does not have Verhoeven’s tone because José Padilha is a very different director. He has his voice that he brings to this movie.”

Padilha’s RoboCop examines highly topical issues of drone politics, the morality of modern-age warfare tactics and its increasing use of remote technology. Padilha says for the backstory, “We created a future that is very close to 2028, in which America, England and China—the big powers—are using drones and autonomous robots for warfare, and each country has its own legislation of whether this is allowed domestically or not. We have this American corporation that builds these machines and sells them to the industrial military complex. They make a lot of money but cannot sell domestically and so are losing a lot of potential profit.”

Michael Keaton portrays the film’s corporate villain, Raymond Sellars. As CEO of OmniCorp, he wants to sell robots in America for law enforcement and eventually sniffs out a loophole. The law mandates that only sentient human beings—entities with feelings— can pull a trigger, so he decides to put a man inside the machine. Smiles Padilha, “This seems like a simple premise, but it entails a lot of things,” becoming passionate as he expands his theory. “We don’t realise this yet but when you automate violence, everything changes. Say a police officer kills a kid by mistake in the line of duty. You can arrest the policeman, you can put him on trial and punish him, and society does that often, everywhere. Say it’s a robot that makes a mistake and kills a kid? It makes no sense to put the robot in jail. So who is accountable? Is it the guy who supplied the robot? The guy who manufactured the robot? Programmed the robot? Is it the software manufacturer? Well, that’s usually done by several different companies, so which company? Accountability gets fuzzy when you have automatic things making decisions like that.”

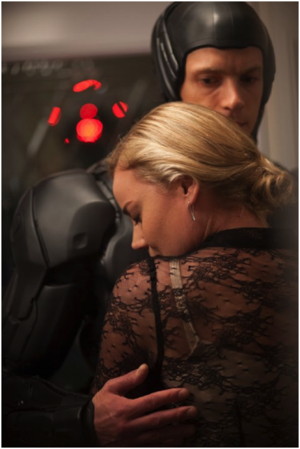

Casting includes Samuel L Jackson as preachy media mogul Pat Novak, Padilha brings in the extreme right-wing. Padilha has expanded the human element by beefing up the role of Alex Murphy’s wife Clara (previously only glimpsed in flashbacks), played by Abbie Cornish. John Paul Ruttan plays David Murphy, Clara and Alex’s young son. “I’ve never seen a kid act like that. Usually kid actors have a tendency to overplay it, but John Paul was minimum, man. The most elegant actor.”

“We needed a great actress to play the wife, Clara Murphy, because she has to react to all of that Abbie is just a great actress.” Even better, they look like each other. When you’ve got Joel next to Abbie and then get JP, it all made sense. It was very important for the family to be credible. You only have twenty minutes to lock into those people and like them, because all of a sudden their universe changes like crazy. Boom! Robot.”

At 1.9m tall, Swedish-American actor Joel Kinnaman (perhaps best known for the TV series The Killing), fills the updated and sleek suit nicely. Padilha says it was important to someone relatively anonymous so that audiences wouldn’t have any pre-conceived expectation. The director elaborates, “Once you put a famous movie star to do a character like this, you immediately create another layer. It becomes X’s RoboCop. Here we needed a great actor, because the guy has to play everything with just his right hand and his face. We did a lot of auditions with a lot of actors, and over and over again, Joel just nailed it.” Jokes Padilha, “I don’t know if it’s because he’s Swedish and they’re into existential things,” he laughs, “but he had it. He’s very charismatic, and he played a cop in The Killing, and can do action scenes, and so on, so he was great for the role.”

Padilha sounds thrilled with the cast he assembled. “Not only did Joel, Abbie and JP do a great job, but Gary Oldman is an amazing actor. I mean, I’ve worked with very good actors in Brazil, but I’ve yet to see someone like Gary Oldman who has a complete technical control of a set. He’s so good, that sometimes a writer can get away with a bad script, because he can make it work. And that’s a danger, but he’s smart enough to know this can be better. Working with Gary was just a pleasure. Then we’ve got Samuel Jackson, who is a Democrat, playing this right-wing crazy! He’s a force of nature. Samuel Jackson walks onto a set and I don’t care who else is on that set, the camera is going boom! Right to him. He had a lot of monologues—so much dialogue to deliver in so little time—and he came in with such domain, and such control of it all and total command of the character. It was just amazing.”

Fans will be pleased to learn that the classic ED209 murder scene is somewhat persevered. Promises Padilha, “We kept several classic moments of the original film, but at the same time we tried to do our own RoboCop because it just makes no sense to try to re-do a classic. That would be silly.”

Fellow Brazilian filmmaker and close friend Fernando Meirelles, (City of God) blabbed to Cinemacom Rapadura that Padilha had confided in him that life during pre-production was “hell.” Over a year ago ScreenCrush quoted Meirelles, translated from his native Portuguese, as saying, “I talked to José Padilha for a week by phone. He will begin filming RoboCop. He is saying that it is the worst experience. For every 10 ideas he has, 9 are cut. Whatever he wants, he has to fight. ‘This is hell here,’ he told me. ‘The film will be good, but I never suffered so much and do not want to do it again.’ He is bitter, but it’s a fighter.”

Padilha brushes the gossip off amiably. “Filmmaking is a collective effort. The great French filmmaker, Jean Renoir, once said, ‘Movies don’t have an author.’ No director is responsible for the face an actor can make that can totally change a scene. Sure, the director has a prominent role because he makes the calls, and picks the actors and the DP and so on, but movies are not totally controlled by the director. It’s not the same thing as painting or writing a book. Did I have a vision for this movie? Yes, but that vision is transformed by the people I am working with. You have Gary Oldman on your set; you want to hear what he thinks. All my movies have been like that; they were all born out everyone getting immersed in the same world, the same story—understanding the story you want to tell then getting together to tell it. And so I think we achieved that. When I say everyone, I’m including the studio too—they have a legitimate interest in the movie, a commercial interest. They’re paying for it. They have their ideas and they take part in the conversation. It has to be like this and it’s like this in any Hollywood movie.”

Gary Oldman, who plays scientist Dr Dennett Norton, asserts that Padilha got to do “everything he wanted to do” on set. “What was interesting to me was that he didn’t just want to remake the first one because it still works.” A fan of the Brazilian director’s previous work, Oldman said, “It’s already got a pedigree, going into it. It’s more appealing—I like this guy, I like his other stuff. It’s him, dipping his toe into pop culture, someone trying something different, but bringing their own sensitivity to it, coming from that world.”

Kinnaman says he found Padilha’s directing style thorough and “Very impressive. José won a couple of big battles and earned the trust from the people who have invested in this. He insisted on a process where we had three weeks with all the actors, going through the whole script and rehearsing every scene, talking about every scene and rewriting the script and getting rid of adolescent bullshit and trying to make it an adult film. I haven’t really had that experience on a movie. Here, all the actors really feel like they are participating and telling the story together.”

As for what percentage of his vision was realized, the director jokingly confides, “Don’t tell anybody, but I didn’t really have a vision,” before adding, “Moviemaking is really about screenwriting and casting, it boils down to that.”

This interview first appeared in Filmink Magazine.