Two extensive photographic exhibitions currently on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center appear, at first glance, to be unlikely companion pieces. HRH Queen Victoria’s devotion to photography is on display in A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography. For Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense, this exhibition is broken into three sections—Dioramas, Portraits and Photogenic Drawings, all of which examine museums and collecting. In it, contemporary photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto’s works are linked to the Queen Victoria exhibition by a single image, namely a large gelatin silver print of a photo of the wax figure of Queen Victoria, taken in 1999 by Sugimoto. Both photographic exhibitions run until June 8, 2014.

A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography.

With important loans held in the Royal Collection, generously lent by Her Majesty The Queen, shown alongside masterpieces from the Getty Museum, the exhibition displays rare daguerreotypes, private portraits of the royal family, and a selection of prints by early masters such as William Henry Fox Talbot, Roger Fenton and Julia Margaret Cameron.

You can also see rare stereographs, stylish ‘cartes des visites’ (aka calling cards, that also served as photographic collectibles) and a massively long lithograph. This unfolded booklet is a detailed reproduction that charts and records the numerous stages of Queen Victoria’s coronation, capturing the pomp and circumstance of this major public event. The exhibition is bookended by a small snippet of moving film of the Queen’s 60th Jubilee celebration.

With its collection of 170 photos and objects, this exhibition charts the Royal Family’s role in supporting the advances of a new technology—photography—as avid patrons. We see a mixture of items that demonstrate Victoria as a young Queen and mother alongside works that were created during her long reign. Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 at the tender age of 18 and reigned until her death, 64 years later, in 1901. During that time, photography was emerging as a new art form. Both Talbot and Daguerre were independently exploring different techniques of this amazing and innovative technology whose object was to permanently capture an image.

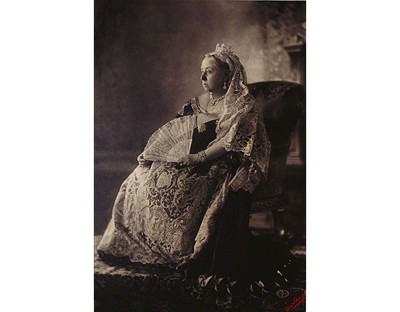

Over the course of her long reign, the queen was photographed as loving mother, devoted wife, grieving widow, and powerful sovereign. She was the first British monarch to have her life fully recorded by the camera, and her portraits became emblematic of an entire age.

Historical background:

At the age of 18, Queen Victoria (1819–1901) ascended the throne of Great Britain and Ireland and was about to turn 20 when the invention of photography was announced—first in Paris, then in London—at the beginning of 1839. The queen and her husband Prince Albert fully embraced the new medium early on, and by 1842 the royal family was collecting photographs. Through their patronage and support, they contributed to the dialogue on photography and were integral to its rise in popularity.

“As the first British monarch to have her life fully recorded by the camera, Victoria’s image became synonymous with an entire age,” explains Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “Now, 175 years later, we take this opportunity to celebrate both the anniversary of photography and the queen’s relationship with it, through a rich collection of images that portray both the evolution of the medium and the monarchy.”

Birth of Photography and Royal Patronage.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert took an interest in photography in the 1840s, which is remarkable given its limited application and dissemination at the time. The first royal photographic portrait—of Albert—was made by William Constable in 1842. While Victoria enjoyed seeing Albert photographed, she was initially apprehensive about being photographed herself. A pair of key images in the exhibition feature Victoria with her children in 1852, sitting for photographer William Edward Kilburn. In the first portrait, the long exposure time created an image in which Victoria’s eyes were closed. Writing in her diary entry for that day, she described her image as “horrid.” She disliked the portrait so much that she scratched the daguerreotype to remove her face. However two days later the queen repeated the exercise and sat before Kilburn’s camera again, only this time she chose to sit in profile wearing a large brimmed bonnet to hide her face.

For many people, the first opportunity of viewing an actual photograph took place in 1851 at the Great Exhibition of the Industry of Works of All Nations, which opened in London at an event presided over by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Among its 13,000 exhibits were 700 photographs housed in a massive iron and glass structure in Hyde Park. The Crystal Palace, as it was known, was documented in a series of daguerreotypes by John Jabez Edwin Mayall. The royal family would continue to support similar displays of photography that took place during the 1850s; in addition, they became patrons of the Photographic Society of London. Queen Victoria’s interest in the medium was effectively a royal seal of approval and her interest facilitated its growing popularity.

During her reign, a number of conflicts were also captured on camera, including the Crimean War and Sepoy Rebellion. The camera, although unable to record live battle, was able to record the before and after effects of conflict, and its images revealed both the tedium and horrors of war in these far off lands. Roger Fenton’s Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855) shows a stretch of land that was frequently attacked by the Russian Army, strewn with cannonballs. Formal military portraits, such as William Edward Kilburn’s Portrait of Lt. Robert Horsely Cockerell (1854) took on a memorial quality for families who lost loved ones.

As the application of photography developed through the course of the 19th century, so too did the medium itself. Many photographic innovations and experimentations occurred, particularly in the first thirty years. From early daguerreotypes and paper negatives, to the popular carte de visite and stereoscopic photography, the latter a technique that gave photographs the illusion of depth through binocular vision, the exhibition surveys these many innovations and accomplishments. Visitors will be able to look through reproductions of stereoscopic devices in the exhibition.

Private Photographs of the Royal Family.

Victoria and Albert shared their passion for photography, not only in exchanging gifts at birthdays and Christmas, but in collecting, organizing, and mounting the family portraits in albums, and would frequently spend evenings working together on assembling these volumes. Victoria would often bring albums and small framed portraits of her family along on her travels. The Getty is displaying a custom-made bracelet she wore that features photographs of her grandchildren.

“As the medium of photography evolved over the years, so did Victoria’s photographic image: she was the camera-shy young mother before she became an internationally recognizable sovereign,” explains Anne Lyden, curator of the exhibition.

In a rare glimpse of these private photographs, the exhibition includes scenes of young royals at play and images in which the royal family appears informal and almost middle-class in their appearance. In an 1854 portrait by Roger Fenton, the casual attire of the queen is disarming. She is wrapped in a tartan shawl and surrounded by four of her children (she would bear nine children in the span of seventeen years). This is not the image of a bejewelled monarch reigning over her empire, but an intimate view of family life. A pair of scissors and a key visible on the chain on her chatelaine suggests practicality and hints at routine household rituals.

Public Photographs, Public Mourning, and State Portraits

Public photographs of the royal family were incredibly popular—the majority of the population would never see a royal in person, and photographs offered a connection to nobility. However, it was not until 1860 that such photographs were available to the public, when John Jabez Edwin Mayall made the first photograph of the queen available for purchase. The event coincided with the rise in popularity of cartes de visite, thin paper photographs mounted on a thick paper card, which, given their small size, were popular for trading and were easily transported. Within days of Mayall’s portrait being issued, over 60,000 orders had been placed, as people were eager to have a glimpse into the private life of the sovereign. Interest in the royal family extended to views of their various royal residences, such as Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, Balmoral Castle, and Osborne House, are also included in the exhibition.

When Albert died suddenly on December 14, 1861, Victoria became a widow at the age of 42 and was in deep mourning for the rest of her life. While she retreated from public life, photographs of her as the bereaved wife were widely available, becoming in effect the queen’s public presence. While the tableau of a grieving widow remained prevalent for the remainder of Victoria’s reign, in the 1870s and 1880s she sat for a number of extremely popular state portraits that preserved her powerful position as monarch. The exhibition includes portraits taken by W. & D. Downey and Gunn & Stewart on the occasion of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, as well as other portraits in which she is seen in full regal attire, complete with royal jewels and crown.

A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography, is on view February 4–June 8, 2014 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. The exhibition was curated by Anne Lyden, international photography curator at the National Galleries of Scotland and former associate curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Getty Publications will issue the accompanying book A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography by Anne Lyden.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense.

Concurrently on view in the Center for Photographs is Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense, which includes Sugimoto’s wax figure portrait of Queen Victoria.

Since the mid-1970s, Hiroshi Sugimoto has used photography to investigate how visual representation interprets and distills history. This exhibition brings together three series by the artist—habitat dioramas, wax portraits, and early photographic negatives—that present objects of historical and cultural significance from various museum collections. By photographing subjects that reimagine or replicate moments from the distant past, Sugimoto critiques the medium’s presumed capacity to portray history with accuracy.

Sugimoto first encountered the elaborate animal dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History after moving to New York in 1974 and began to focus his camera on individual scenes shortly after. Omitting the didactic materials surrounding each display, these works heighten the illusion that the animals were photographed in their natural habitats. While each photograph appears to be a candid moment captured by an experienced nature photographer, the subjects depicted will hold their poses indefinitely.

A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense

J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center

1200 Getty Center Drive,

Los Angeles, California.

Both photographic exhibitions run until June 8, 2014.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects in seven distinct areas, including Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts, and photographs gathered internationally. The Museum’s mission is to make the collection meaningful and attractive to a broad audience by presenting and interpreting the works of art through educational programs, special exhibitions, publications, conservation, and research.

Visiting the Getty Center:

The Getty Center is open Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. It is closed Monday and major holidays. Admission to the Getty Center is always free. Parking is $15 per car, but reduced to $10 after 5 p.m. on Saturdays and for evening events throughout the week. No reservation is required for parking or general admission. Reservations are required for event seating and groups of 15 or more. Please call (310) 440-7300 (English or Spanish) for reservations and information. The TTY line for callers who are deaf or hearing impaired is (310) 440-7305. The Getty Center is at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California. Same day parking at both Museum locations (Getty Center and Getty Villa) is available for $15 through the Getty’s Pay Once, Park Twice program.

Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. Income generated from admissions and from associated commercial activities contributes directly to The Royal Collection Trust, a registered charity. The aims of The Trust are the care and conservation of the Royal Collection, and the promotion of access and enjoyment through exhibitions, publications, loans and educational programmes. Royal Collection Trust’s work is undertaken without public funding of any kind.

The Royal Collection is among the largest and most important art collections in the world, and one of the last great European royal collections to remain intact. It comprises almost all aspects of the fine and decorative arts, and is spread among some 13 royal residences and former residences across the UK, most of which are regularly open to the public. The Royal Collection is held in trust by the Sovereign for her successors and the nation, and is not owned by The Queen as a private individual.

At The Queen’s Galleries in London and Edinburgh and in the Drawings Gallery at Windsor Castle, aspects of the Collection are displayed in a programme of temporary exhibitions. Many works from the Collection are on long-term loan to institutions throughout the UK, and short-term loans are frequently made to exhibitions around the world as part of a commitment to public access and to show the Collection in new contexts.

Explore the Royal Collection here.