CHINGLISH

Henry David Hwang Takes us on an Adventure in Modern China

Review by Deborah Klugman

When playwright Henry David Hwang traveled to China in 2005, he visited a brand new cultural arts center. It was a craftsmen’s showcase, with beautiful Brazilian wood, expensive Italian marble and a state-of-the-art sound system. There was one major problem, however: the wording on the signs. Sporting translations from Mandarin into English, many sounded farcical and outrageous. One, posted outside the men’s handicapped restroom, identified the facility as the “Deformed Men’s Toilet.” Hwang noted these comic discrepancies and integrated them with other observations and insights gleaned from his sojourn. The toilet mistranslation eventually appears as a laugh line in Chinglish, his entertaining and thoughtful play whose themes involve language, love, politics and culture in our rapidly changing world.

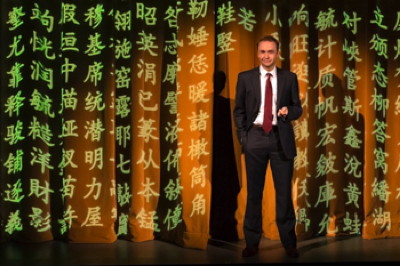

Directed by Leigh Silverman (who directed the show both on Broadway and at Chicago’s Goodman Theater), Chinglish centers on the experience of an American businessman from the Midwest named Daniel (Alex Moggridge), who travels to a small city in China to try to secure a contract for his flailing family business, which is sign making. To succeed, Daniel must charm his way into the good graces of the city’s antediluvian minister of culture, Cai (Raymond Ma). Unable to speak Mandarin, he hires Peter (Brian Nishii), a Westerner living in China who speaks the language fluently. Although Peter passes himself off to Daniel as a businessman, we later learn that, like nearly everyone and everything else Daniel encounters, poseur Peter is not what he seems.

Despite Peter’s facility with Mandarin, Daniel’s first interview with Cai is fraught with miscommunication: His efforts to present himself in a positive light are undercut by the wacky translations of an inept Chinese interpreter (Celeste Den), and equally as much by the minister’s inclination to shift their conversation away from the business at hand to topics he prefers: e.g. the wonders of Chicago, which he had once visited, and the virtues of a topnotch steak. Hwang lays out some of the play’s major themes in this early humorous scene, which illuminates not only the distortions that can and do arise when you translate from one language to the next but, more significantly, the gaping disparities in social and business mores between our American culture and that of the Chinese. While the quintessentially American Daniel speaks to the point, Cai talks around it, feigning the modesty and self-effacement that is the expected norm within his circle, even as he depends on the interjections of underlings and associates to sing his praises. And the reasons that Daniel is auditioning his company there in the first place speak to the turnaround in relations between a rising China and a debt-ridden U.S.

Daniel’s quest turns considerably more serpentine when he is surreptitiously approached by Cai’s second in command, Xi Yan (Michelle Krusiec), who confides that her superior has no intention of offering Daniel the contract but instead plans to award it to his sister-in-law, who’s been lobbying hard for years. A smart stunning woman, Xi offers to help the bewildered Daniel circumvent Cai’s plan. A down-home mid-level exec from Cleveland, Daniel is puzzled as to why she would undertake to help him (Because “you honest man” Xi communicates in her broken, entry level English.) He’s dazzled as well. Soon the pair is frequenting hotel rooms together, going at it hot and heavy between strategy sessions that more and more seem to irk Xi and spoil her fun.

Much of our fun develops watching the two of them struggle to relate without the benefit of language: she’d studied English for 6 months while he speaks no Mandarin at all. As the enigmatic Xi, Krusiec’s glittering quasi-dragon lady portrait is one of the production’s highlights. Moggridge, depicting an ingenuous stranger in a strange land, delivers the perfect foil, with Daniel’s unsettling education into the wherefores of business and romance in modern Chinese culture meshing into our own.

Some of the supporting performances aren’t quite as on target. Ma’s oily aging minister is on the mark, but as Peter, Nishii struck me as stiff and awkward and not nearly as glib as his aspiring speculator might have been. Den overdoes the interpreter’s truculence, playing her disgruntled ineptitude for laughs when a more subdued cluelessness might have been more effective. But then, that whole first encounter between Daniel and Cai is more a comic gambit than anything else. The meatier and more intriguing aspects of the plot emerge later on.

Not every particular in the plot hold together, either. At one point Daniel reveals that he was once an operant at Enron – a name with which Cai is familiar and which impresses him and stirs his enthusiasm rather than the opposite. The point is to illustrate the amoral admiration of the Chinese establishment for success, which is fair enough. But it’s a detail that doesn’t jibe with the rest of Daniel’s frank and forthright demeanor. It seems contrived.

Still, inconsistencies can be overlooked in a play that mixes entertainment and cultural enlightenment in a clever way. Chinglish has something to say about many things: language, marriage, identity and, most importantly, the elusiveness of truth.

For that alone, it’s worth checking out.

Photos by Henry DiRocco/SCR.

Chinglish

Where: South Coast Repertory

655 Town Center Drive,

Costa Mesa

When: 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays-Wednesdays,

8 p.m. Thursdays-Fridays, 2:30 and 8 p.m.

Saturdays, 2:30 and 7:30 p.m.

Sundays. (Call for exceptions.)

Runs through Feb. 24. 2013

Tickets: $29-$70

Contact: (714) 708-5555

Running time: approx two hours